-40%

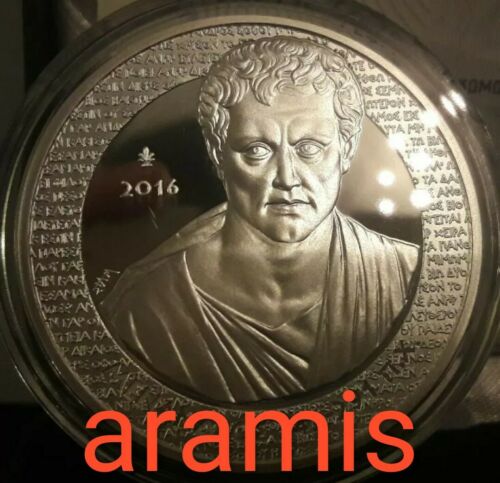

Best price 🅰️ SILVER PROOF 🅰️ GREECE 10 Euro 2016 MENANDER 🅰️ ancient GRECE

$ 73.39

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

GREECE 10 EURO 2016 MENANDEROriginal Proof coin from the National bank of Greece.

2000 Coins Mintage.

925‰ SILVER

34.10 Grams

40.00 mm Diameter

Comes with Certificate Of Authenticity (C.O.A.) and Original Box.

ΓΙΑ ΕΛΛΑΔΑ ΓΙΝΕΤΑΙ ΚΑΙ ΑΝΤΙΚΑΒΟΛΗ Η ΚΑΤΑΘΕΣΗ/ΜΕΤΑΦΟΡΑ ΣΕ ΤΡΑΠΕΖΑ.

Επικοινωνήστε για λεπτομέρειες.

The item on the pictures is the one that you will receive.

Look carrefully and judge for your self for the quallity and the grade.

S&h is .90 for all the world.

Registered mail with international tracking number.

Each additional light weight item is free.

For coins with box+coa,

postage can be conbined for each.

BID WITH CONFIDENCE.

.

SELLER with 100% POSITIVE FEEDBACK.

Menander

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For other uses, see Menander (disambiguation).

Menander

Bust of Menander. Marble, Roman copy of the Imperial era after a Greek original (ca. 343–291 BC).

Born 342/41 BC

Kephisia, Athens

Died c. 290 BC

Education Student of Theophrastus at the Lyceum

Information

Genre New Comedy

Notable work(s)

Dyskolos

Samia

Menander (/məˈnændər/; Greek: Μένανδρος, Menandros; c. 342/41 – c. 290 BC) was a Greek dramatist and the best-known representative of Athenian New Comedy.[1] He wrote 108 comedies [2] and took the prize at the Lenaia festival eight times.[3] His record at the City Dionysia is unknown but may well have been similarly spectacular.

One of the most popular writers of antiquity, his work was lost during the Middle Ages and is known in modernity in highly fragmentary form, much of which was discovered in the 20th century. Only one play, Dyskolos, has survived almost entirely.

Contents

1 Life and work2 Loss of his work3 20th-century discoveries4 Famous quotations5 Comedies5.1 More complete plays5.2 Only fragments available6 Standard editions7 See also8 Notes9 References10 External linksLife and work

Roman, Republican or Early Imperial, Relief of a seated poet (Menander) with masks of New Comedy, 1st century B.C. – early 1st century A.D., Princeton University Art Museum

Menander was the son of well-to-do parents; his father Diopeithes is identified by some with the Athenian general and governor of the Thracian Chersonese known from the speech of Demosthenes De Chersoneso. He presumably derived his taste for comic drama from his uncle Alexis.[4]

He was the friend, associate, and perhaps pupil of Theophrastus, and was on intimate terms with the Athenian dictator Demetrius of Phalerum.[5] He also enjoyed the patronage of Ptolemy Soter, the son of Lagus, who invited him to his court. But Menander, preferring the independence of his villa in the Piraeus and the company of his mistress Glycera, refused.[6] According to the note of a scholiast on the Ibis of Ovid, he drowned while bathing,[7] and his countrymen honored him with a tomb on the road leading to Athens, where it was seen by Pausanias.[8] Numerous supposed busts of him survive, including a well-known statue in the Vatican, formerly thought to represent Gaius Marius.

His rival in dramatic art (and supposedly in the affections of Glycera) was Philemon, who appears to have been more popular. Menander, however, believed himself to be the better dramatist, and, according to Aulus Gellius,[9] used to ask Philemon: "Don't you feel ashamed whenever you gain a victory over me?" According to Caecilius of Calacte (Porphyry in Eusebius, Praeparatio evangelica[10]) Menander was accused of plagiarism, as his The Superstitious Man was taken from The Augur of Antiphanes, but reworkings and variations on a theme of this sort were commonplace and so the charge is a complicated one.

How long complete copies of his plays survived is unclear, although 23 of them, with commentary by Michael Psellus, were said to still have been available in Constantinople in the 11th century. He is praised by Plutarch (Comparison of Menander and Aristophanes)[11] and Quintilian (Institutio Oratoria), who accepted the tradition that he was the author of the speeches published under the name of the Attic orator Charisius.[12]

Seated portrait of Menander, Roman fresco from the Casa del Menandro in Pompeii

An admirer and imitator of Euripides, Menander resembles him in his keen observation of practical life, his analysis of the emotions, and his fondness for moral maxims, many of which became proverbial: "The property of friends is common," "Whom the gods love die young," "Evil communications corrupt good manners" (from the Thaïs, quoted in 1 Corinthians 15:33). These maxims (chiefly monostichs) were afterwards collected, and, with additions from other sources, were edited as Menander's One-Verse Maxims, a kind of moral textbook for the use of schools.

The single surviving speech from his early play Drunkenness is an attack on the politician Callimedon, in the manner of Aristophanes, whose bawdy style was adopted in many of his plays.

Menander found many Roman imitators. Eunuchus, Andria, Heauton Timorumenos and Adelphi of Terence (called by Caesar "dimidiatus Menander") were avowedly taken from Menander, but some of them appear to be adaptations and combinations of more than one play. Thus in the Andria were combined Menander's The Woman from Andros and The Woman from Perinthos, in the Eunuchus, The Eunuch and The Flatterer, while the Adelphi was compiled partly from Menander and partly from Diphilus. The original of Terence's Hecyra (as of the Phormio) is generally supposed to be, not by Menander, but Apollodorus of Carystus. The Bacchides and Stichus of Plautus were probably based upon Menander's The Double Deceiver and Brotherly-Loving Men, but the Poenulus does not seem to be from The Carthaginian, nor the Mostellaria from The Apparition, in spite of the similarity of titles. Caecilius Statius, Luscius Lanuvinus, Turpilius and Atilius also imitated Menander. He was further credited with the authorship of some epigrams of doubtful authenticity; the letters addressed to Ptolemy Soter and the discourses in prose on various subjects mentioned by the Suda[13] are probably spurious.Loss of his work

Most of Menander's work did not survive the Middle Ages, except as short fragments. Michael Psellos might be the last writer who may have known more than we do today.[14][not in citation given] Federico da Montefeltro's library at Urbino reputedly had "tutte le opere", a complete works, but its existence has been questioned and there are no traces after Cesare Borgia's capture of the city and the transfer of the library to the Vatican.[15]

Until the end of the 19th century, all that was known of Menander were fragments quoted by other authors and collected by Augustus Meineke (1855) and Theodor Kock, Comicorum Atticorum Fragmenta (1888). These consist of some 1650 verses or parts of verses, in addition to a considerable number of words quoted from Menander by ancient lexicographers.20th-century discoveries

A papyrus fragment of the Perikeiromene 976–1008 (P. Oxy. 211 II 211, 1st or 2nd century CE).

This situation changed abruptly in 1907, with the discovery of the Cairo Codex, which contained large parts of the Samia; the Perikeiromene; the Epitrepontes; a section of the Heros; and another fragment from an unidentified play. A fragment of 115 lines of the Sikyonioi had been found in the papier mache of a mummy case in 1906.

In 1959, the Bodmer papyrus was published containing Dyskolos, more of the Samia, and half the Aspis. In the late 1960s, more of the Sikyonioi was found as filling for two more mummy cases; this proved to be drawn from the same manuscript as the discovery in 1906, which had clearly been thoroughly recycled.[16]

Other papyrus fragments continue to be discovered and published.

Menander. Roman copy, after original by Kephisodotos the Younger and Timarchos, sons of Praxiteles, of 4th century B.C. Marble. The Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia.

In 2003, a palimpsest manuscript, in Syriac writing of the 9th century, was found where the reused parchment comes from a very expensive 4th-century Greek manuscript of works by Menander. The surviving leaves contain parts of the Dyskolos and 200 lines of another, so far unidentified, piece by Menander.[14][17]Famous quotations

The apostle Paul in 1 Corinthians 15:33 quotes Menander in the text "Bad company corrupts good character" (NIV) who probably derived this from Euripides (Socrates, Ecclesiastical History, 3.16).

"He who labors diligently need never despair, for all things are accomplished by diligence and labor." — Menander

"Ἀνερρίφθω κύβος" (anerriphtho kybos), best known in English as "the die is cast" or "the die has been cast", from the mis-translated Latin "iacta alea est" (itself better-known in the order "Alea iacta est"); a correct translation is "let the die be cast" (meaning "let the game be ventured"). The Greek form was famously quoted by Julius Caesar upon committing his army to civil war by crossing the River Rubicon.[18] The popular form "the die is cast" is from the Latin iacta alea est, a mistranslation by Suetonius, 121 CE. According to Plutarch, the actual phrase used by Julius Caesar at the crossing of the Rubicon was a quote in Greek from Menander's play Arrhephoros, with the different meaning "Let the die be cast!".[19] See discussion at "the die is cast" and "Alea iacta est".

He [Caesar] declared in Greek with loud voice to those who were present 'Let the die be cast' and led the army across. (Plutarch, Life of Pompey, 60.2.9)[20]

Lewis and Short,[21] citing Casaubon and Ruhnk, suggest that the text of Suetonius should read Jacta alea esto, which they translate as "Let the die be cast!", or "Let the game be ventured!". This matches Plutarch's third-person perfect imperative ἀνερρίφθω κύβος (anerrhiphtho kybos).